La Repubblica democratica del tondo

The roundabout is an institution of direct vehicular democracy; it is the realization of egalitarian utopia on the road; it is a place where all motorized vehicles can access without discrimination of sex, race, language, religion, political opinions, personal, and social conditions. The roundabout is responsibility, participation, freedom. It is the Democratic Republic of the Roundabout. Traffic lights, on the other hand, treat us like foolish subjects. They impose stopping and moving with the bureaucratic monotony. The roundabout is a step forward: it establishes two simple rules – those outside wait, those inside proceed – and lets everyone regulate themselves. It is no coincidence that the first modern roundabout, the Columbus Circle in New York City, was born in 1903, a few years before Maria Montessori opened her children's house in Rome. The roundabout is finely pedagogical.

Text by Emanuele Galesi, continue below...

Text by Emanuele Galesi, continue below...

PUBLICATIONS

Urbano Magazine

Marsèll

Urbano Magazine

Marsèll

...

Matteo de Mayda knows roundabouts well. Born in Treviso around the mid-1980s, he saw them proliferate during his youth, in the joyful Veneto that scattered its artifacts, from warehouses to commercial hubs. As a son of the motorized Northern Macroregion, he knows that the profound meaning of the roundabout is not vehicular, but spatial. It is space created from nothing, it is the island that wasn't there before and is now, and as such, it must be colonized. How? From the artificial vine tendrils in Vicenza to the colossal sphinx in Turin, the Macroregion is dotted with works that guard these atolls in the sea of asphalt. Monuments dedicated to industry, music, road safety, or even olive trees, hedges, or palm trees: without a predetermined plan, roundabouts have also become means of mass communication.

When two years ago de Mayda found himself in front of the Algerian roundabouts around the city of Tindouf, he felt at home. It's like when we meet one of our compatriots abroad: maybe it annoys us a little, but it still excites us. He was traveling through the refugee camps where the Sahrawi are hosted, a population that has mostly lived far from their own land for forty years, occupied by Morocco. They are stationary refugees; in Algeria, they have rebuilt a community in exile of 150,000 people. An organized community, but one that still needs international aid to sustain itself. In the midst of the desert, along the roads connecting the different camps, the photographer is struck by a first sight: two teapots with as many cups, set in the middle of a roundabout surmounted by a large brazier. Tea in the desert, between cinema and Saharan tradition, it's hard to imagine something more didactic. But on the road, there is more: after the teapots, here come three thin crossed poles, from which hangs an indistinct shape of which the animal nature is intuited. The locals explain that the dangling sack is a gherba, a goatskin bag used to carry water during journeys across the Sahara. The third roundabout requires further interpretative effort: geometric figures, elegantly decorated, embellish a landscape of sand, pylons, and distant low buildings. What are they? They are traditional jewels and they fit perfectly into the identity that marks the streets of the place. De Mayda is undergoing an intensive course of local customs and traditions, without explanatory signs and without the classic museum. Those who know, recognize and recognize themselves, while those from outside need to be guided through the symbols. The effect is alienating and reaches its peak with the roundabout where two blue hands clasp in a gesture of cooperation, help, peace, on a base decorated with white doves. The opposite of the experience of those living in the camps around Tindouf, settlements resulting from a war that has never ended.

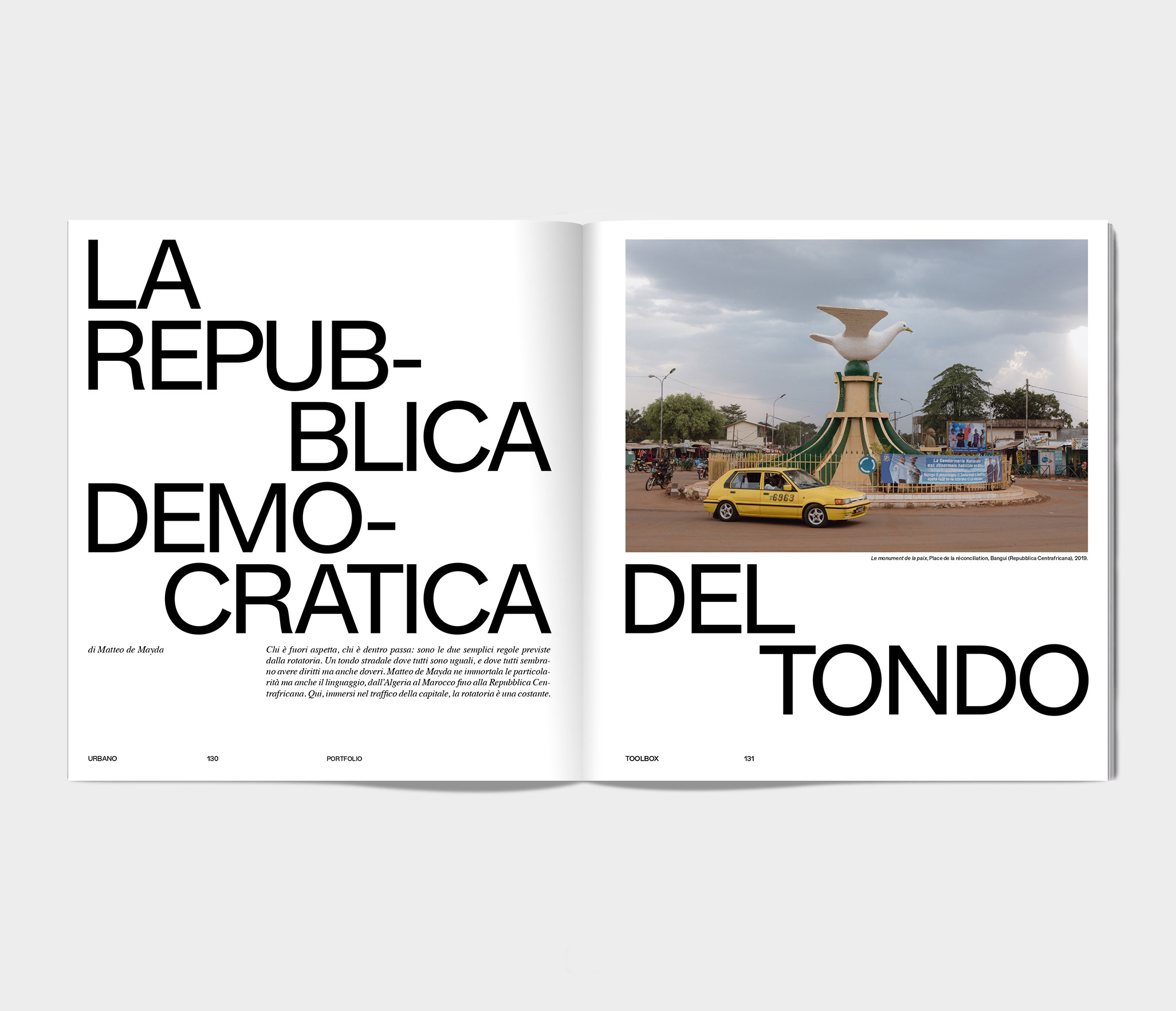

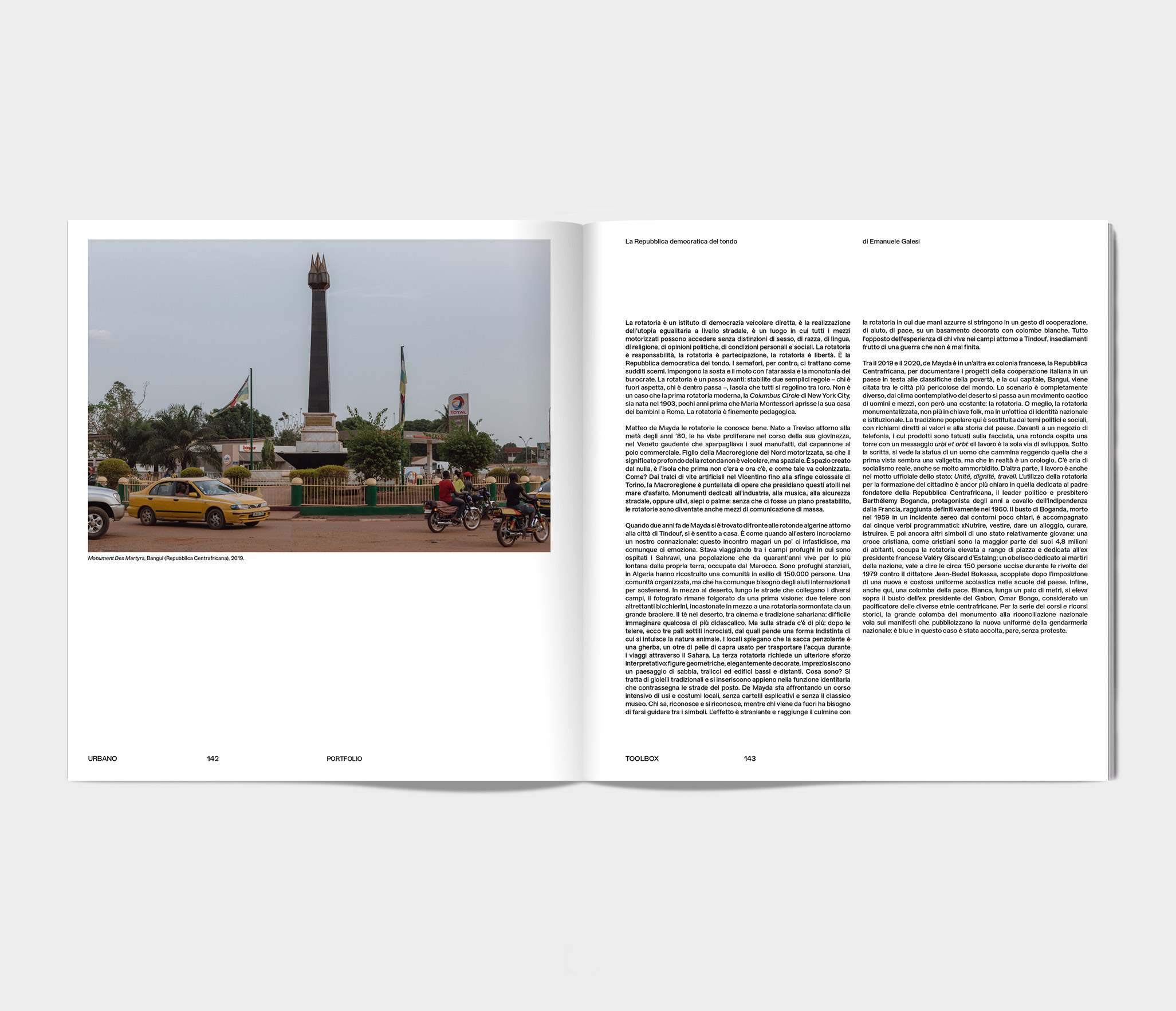

Between 2019 and 2020, de Mayda is in another former French colony, the Central African Republic, to document Italian cooperation projects in a country leading the poverty rankings, whose capital, Bangui, is cited among the most dangerous cities in the world. The scenario is completely different; from the contemplative climate of the desert, we move to a chaotic movement of men and vehicles, with a constant: the roundabout. Or rather, the monumentalized roundabout, no longer in a folk key, but from a national and institutional perspective. Popular tradition here is replaced by political and social themes, with direct references to the values and history of the country. In front of a telephone shop, whose products are tattooed on the facade, a roundabout hosts a tower with a message for the city and the world: "Work is the only path to development." Under the inscription, you can see the statue of a man walking, holding what at first glance seems like a briefcase, but is actually a clock. There is an air of real socialism, although much softened. On the other hand, work is also in the state's official motto: "Unity, dignity, work." The use of the roundabout for citizen education is even clearer in the one dedicated to the founding father of the Central African Republic, the political leader and priest Barthélemy Boganda, a protagonist of the years around independence from France, definitively achieved in 1960. Boganda's bust, who died in 1959 in a mysterious air crash, is accompanied by five programmatic verbs: "Feeding, clothing, providing shelter, healing, educating." And then, there are other symbols of a still relatively young state: a Christian cross, as most of its 4.8 million inhabitants are Christians, occupies the roundabout elevated to the rank of square and dedicated to the former French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing; an obelisk dedicated to the martyrs of the nation, namely the about 150 people killed during the 1979 riots against dictator Jean-Bedel Bokassa, which broke out after the imposition of a new and expensive school uniform in the country's schools. Finally, also here, a dove of peace. White, a couple of meters long, it rises above a bust of the former president of Gabon, Omar Bongo, considered a peacemaker of the different Central African ethnic groups. In the series of historical recurrences, the large dove of the monument to national reconciliation flies over posters advertising the new uniform of the national gendarmerie: it is blue and in this case it seems to have been accepted without protests.

Matteo de Mayda knows roundabouts well. Born in Treviso around the mid-1980s, he saw them proliferate during his youth, in the joyful Veneto that scattered its artifacts, from warehouses to commercial hubs. As a son of the motorized Northern Macroregion, he knows that the profound meaning of the roundabout is not vehicular, but spatial. It is space created from nothing, it is the island that wasn't there before and is now, and as such, it must be colonized. How? From the artificial vine tendrils in Vicenza to the colossal sphinx in Turin, the Macroregion is dotted with works that guard these atolls in the sea of asphalt. Monuments dedicated to industry, music, road safety, or even olive trees, hedges, or palm trees: without a predetermined plan, roundabouts have also become means of mass communication.

When two years ago de Mayda found himself in front of the Algerian roundabouts around the city of Tindouf, he felt at home. It's like when we meet one of our compatriots abroad: maybe it annoys us a little, but it still excites us. He was traveling through the refugee camps where the Sahrawi are hosted, a population that has mostly lived far from their own land for forty years, occupied by Morocco. They are stationary refugees; in Algeria, they have rebuilt a community in exile of 150,000 people. An organized community, but one that still needs international aid to sustain itself. In the midst of the desert, along the roads connecting the different camps, the photographer is struck by a first sight: two teapots with as many cups, set in the middle of a roundabout surmounted by a large brazier. Tea in the desert, between cinema and Saharan tradition, it's hard to imagine something more didactic. But on the road, there is more: after the teapots, here come three thin crossed poles, from which hangs an indistinct shape of which the animal nature is intuited. The locals explain that the dangling sack is a gherba, a goatskin bag used to carry water during journeys across the Sahara. The third roundabout requires further interpretative effort: geometric figures, elegantly decorated, embellish a landscape of sand, pylons, and distant low buildings. What are they? They are traditional jewels and they fit perfectly into the identity that marks the streets of the place. De Mayda is undergoing an intensive course of local customs and traditions, without explanatory signs and without the classic museum. Those who know, recognize and recognize themselves, while those from outside need to be guided through the symbols. The effect is alienating and reaches its peak with the roundabout where two blue hands clasp in a gesture of cooperation, help, peace, on a base decorated with white doves. The opposite of the experience of those living in the camps around Tindouf, settlements resulting from a war that has never ended.

Between 2019 and 2020, de Mayda is in another former French colony, the Central African Republic, to document Italian cooperation projects in a country leading the poverty rankings, whose capital, Bangui, is cited among the most dangerous cities in the world. The scenario is completely different; from the contemplative climate of the desert, we move to a chaotic movement of men and vehicles, with a constant: the roundabout. Or rather, the monumentalized roundabout, no longer in a folk key, but from a national and institutional perspective. Popular tradition here is replaced by political and social themes, with direct references to the values and history of the country. In front of a telephone shop, whose products are tattooed on the facade, a roundabout hosts a tower with a message for the city and the world: "Work is the only path to development." Under the inscription, you can see the statue of a man walking, holding what at first glance seems like a briefcase, but is actually a clock. There is an air of real socialism, although much softened. On the other hand, work is also in the state's official motto: "Unity, dignity, work." The use of the roundabout for citizen education is even clearer in the one dedicated to the founding father of the Central African Republic, the political leader and priest Barthélemy Boganda, a protagonist of the years around independence from France, definitively achieved in 1960. Boganda's bust, who died in 1959 in a mysterious air crash, is accompanied by five programmatic verbs: "Feeding, clothing, providing shelter, healing, educating." And then, there are other symbols of a still relatively young state: a Christian cross, as most of its 4.8 million inhabitants are Christians, occupies the roundabout elevated to the rank of square and dedicated to the former French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing; an obelisk dedicated to the martyrs of the nation, namely the about 150 people killed during the 1979 riots against dictator Jean-Bedel Bokassa, which broke out after the imposition of a new and expensive school uniform in the country's schools. Finally, also here, a dove of peace. White, a couple of meters long, it rises above a bust of the former president of Gabon, Omar Bongo, considered a peacemaker of the different Central African ethnic groups. In the series of historical recurrences, the large dove of the monument to national reconciliation flies over posters advertising the new uniform of the national gendarmerie: it is blue and in this case it seems to have been accepted without protests.